Reimagining Peranakan Designs

Words by Stephanie Peh and Tanya Singh

A new generation of Singaporean designers are reinterpreting the Peranakan heritage through their work, inspiring new ways of perceiving the cultural identity.

The Peranakan ethnicity traces back to the 15th century when foreign traders settled in Singapore, Penang or Malacca, and married local Malay women. Their offsprings identified as Peranakan Chinese (Straits-Chinese), Peranakan Indians (Chitty Melaka) or Peranakan Indian Muslim. It is a hybrid culture with Chinese, Malay and Western influences, mixing the best of two worlds. For instance, its cuisine, also known as Nyonya food—named after the women who made them—is a mix of Chinese cooking techniques and Indonesian or Malay ingredients, resulting in rich and flavorful dishes.

Peranakan aesthetic can be seen in traditional clothing like the kebaya, which is laced with embroidery patterns and matched with hand-beaded slippers. The traditional Peranakan house features polychromatic colors, floral and animal motifs on its facade with ornamental interior furnishings. It is eclectic yet elegant; maximalist yet tasteful, hinting at the Peranakan people's affluence back in the day.

Peranakan culture declined during the Second World War but was subsequently revived to its former prestige, cherished by many today. In fields of art and design where explorations of identity are inevitable, some Singaporean or Singapore-based artists and designers have looked toward the ethnic group for inspiration in manners of expression.

Spotted Nonya Kumcheng by Hans Tan

"The nature of "Peranakan-ness" is the idea of "intermix", which is different from the idea of "blending" where elements amalgamate into each other to form something new, but here, mixture points to a new thing while former elements are still largely appreciable," designer and educator Hans Tan says thoughtfully. For his Spotted Nyonya series, traditional Peranakan porcelain vessels were masked with a dotted motif before being sandblasted and erased, unveiling white porcelain and rendering the original multi-colored motifs in an elegant dotted pattern. This technique imbues traditional homewares with an intriguing mystique without stripping away its identity. Even though parts of it have been removed, the vessels are still recognizable, yet befitting for a modern context.

"Beauty is an excuse for me to play with materials and poke at collective memory," he says. However, Tan is cautious that while nostalgia encourages historical appreciation, it does not drive change. In fact, nostalgia could be detrimental to evolution. "I believe that it's more meaningful if one thinks about how to transform the past and connect it to the present. It's not about bringing back an image, but about finding the position where both the past and present can exist together purposefully," he explains. Tan's work offers new ways of perceiving the Peranakan heritage. "It's a contradiction to its roots if transformation comes to a standstill," he quips.

Left to right: The Peranakan Desk Mirror and The Peranakan Side Table by ipse ipsa ipsum

Known to combine modern materials with traditional craftsmanship, furniture brand ipse ipsa ipsum expressed Peranakan aesthetics with production techniques atypical to the culture. While traditional Peranakan furniture pieces were often made of wood, ipse ipsa ipsum considered other materials to enhance functionality. The bone and resin inlaid Peranakan Side Table features cultural motifs that can be found throughout Singapore and Malaysia.

The Peranakan Desk Mirror showcases attractive patterns materialized through bone inlays—one of the brand's signature craft from India. The intricate pattern is designed in collaboration with Jeremy Sun. "We translated Peranakan aesthetic by combining Indian floral patterns, Chinese Bird Paintings, and Malay-style bold colors that bespeak centuries of cultural interactions," says Saurabh Mangla, the founder of ipse ipsa ipsum.

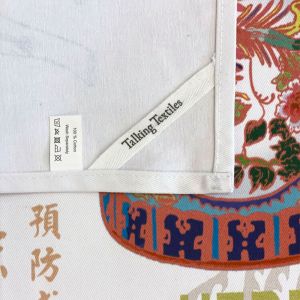

There are other designers and creators who have explored the Peranakan aesthetics by injecting them into decorative items that serve as cultural totems. Local mixed media artist, Deborah McKellar, the founder of Talking Textiles, takes inspiration from Singapore's exotic and bustling city with its juxtaposition of the old and the new. Her textile artworks are characterized by their representation of shophouses in bold colors, layers of stitch, remnants of fabric, silk screened images and printed patterns.

Left to right: The Embroidered Peranakan Tile Cushion Cover and The "Peranakan Kitchen" Glass Trivet by Talking Textiles.

Comprising of montages of seemingly contrasting visuals taken on the streets, the manner in which artist and designer Louise Hill executes her artworks is aptly similar to the Peranakan way. Her sell-out piece, Singapore Shophouses in Heritage Brights combines images of Peranakan shophouses, objects synonymous with the culture like tea caddies and tiffin carriers and decorative layers of photographed embroideries and tiles. Her other piece, Singapore Streets, portrays the grittier and more traditional side of the culture, combining the streetscape of Joo Chiat, Geylang and Chinatown, depicting everyday life on a micro and macro level. Hill's work seems to archive the scenes of modern-day Peranakan culture in an art form. Packed with intricate details, these pieces tease out a sense of wanderlust and curiosity.

Singapore Streets Art Print by Louise Hill Design

When Hill first arrived in Singapore, she resided in one of the heritage shophouses on Koon Seng, which is a picturesque street to admire quaint Peranakan houses. Located in proximity to the Joo Chiat and Katong area known for Peranakan culture, it is where scrumptious Nyonya food and kueh (cake or snack) can be tasted. Venturing off the beaten path, Mangla recommends the Bukit Brown Cemetery, a unique place to view ceramic Peranakan tiles. He also recommends Emerald Hill where architectural and design lovers can study the facades of heritage shophouses of varying styles. To get an idea of what the interior of these houses was like in the past, one can visit the NUS Baba House, a century-old property with a bright-blue facade, a swinging fence door and a Chinese calligraphic signboard that translates to 'The Glory of Lineage'. "In it, you get to experience, to a large extent, the authenticity of the space, and a fascinating collection of furniture and objects, including the original "peephole" from the second level that gave female household members a view of guests at the sitting hall on the ground floor. The top floor of the museum is juxtaposed by a gallery space where contemporary works relevant to Peranakan culture is exhibited," reveals Tan.

Singapore shophouses on Koon Seng Road. Photography credit: Amos Lee

In a young nation like Singapore, where there is a lack of definitive unifying components that make a nation's identity distinct, the constant search for identity sometimes leads one to better understand Peranakan culture and history. Even for people who do not belong to the ethnicity, it is inherently relatable to Singaporeans as it assimilates and absorbs cultural differences with openness.

HK$

HK$ SG$

SG$ US$

US$