Know Your Asian Craft: Paper

Words by: Ashlyn Chak

Asian aesthetics have become mainstream and it is common to see Buddha statues and batik cushions in many modern households. But there's much more to Asian decorative arts than meets the eye. In this series, we dive into different traditional crafts from Asia, examining their roots, histories, and stories – along with how they continue to evolve and define design today.

Before the popularization of the internet, paper was the main medium of communication. Even today, paper occupies our everyday life in the forms of bills, books, clothing tags... and even the things some may not immediately notice, such as wallpaper, furniture, and decorations — from Chinese lanterns to Japanese Shoji windows — adding ambience and personality to spaces. Nowadays, while industrial machinery manufactures most paper we use, traditional, handmade paper survives as a specialized craft of irreplaceable textures, aesthetics, and stories.

Regarding the origin of paper, Egypt's papyrus may come to mind for some, but the first true papermaking process was actually developed in ancient China's Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) before the secret of hemp sprouted along the silk road. Fast forward to modern-day Asia, many traditional papermaking practices have become heritage crafts — from China's xuan paper to Japan's washi paper and India's wasli paper, these unique art forms are a testament to humankind's everlasting desire for beauty and meaning, despite new cheaper and easier ways of producing paper.

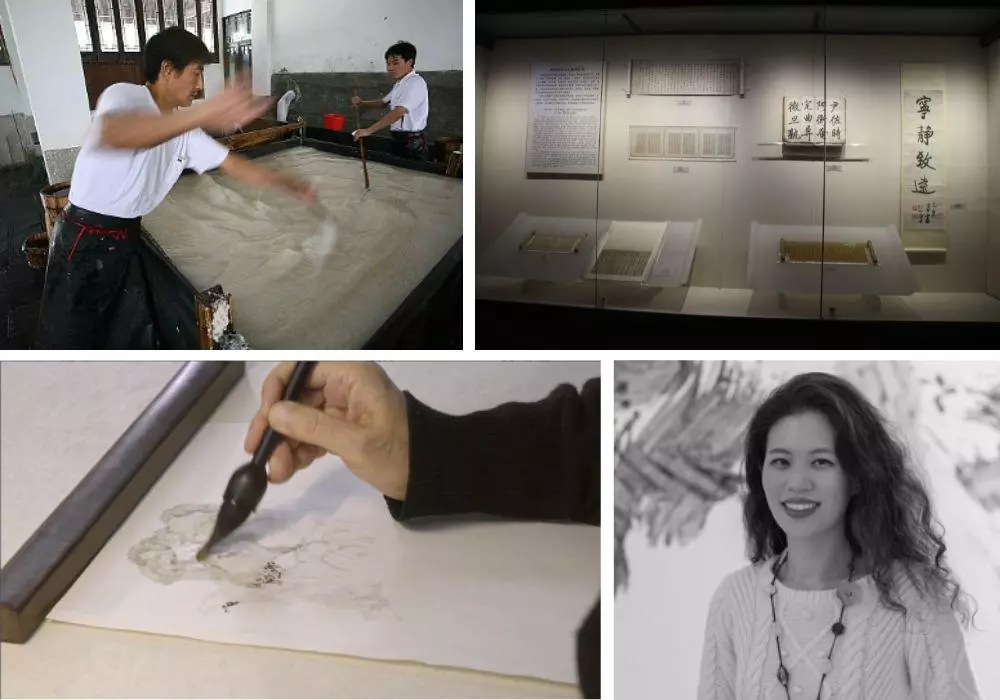

Soft and fine-textured yet tensile and moth-resistant, xuan paper is the reason many ancient Chinese scrolls are preserved well for our appreciation. As described by a xuan craftsman, "The fibre takes the rhombic shape under the microscope, so when the ink and water are brushed onto the paper, the paper can hold them very tightly." For centuries, it has been used in China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam for calligraphy, painting, and architecture.

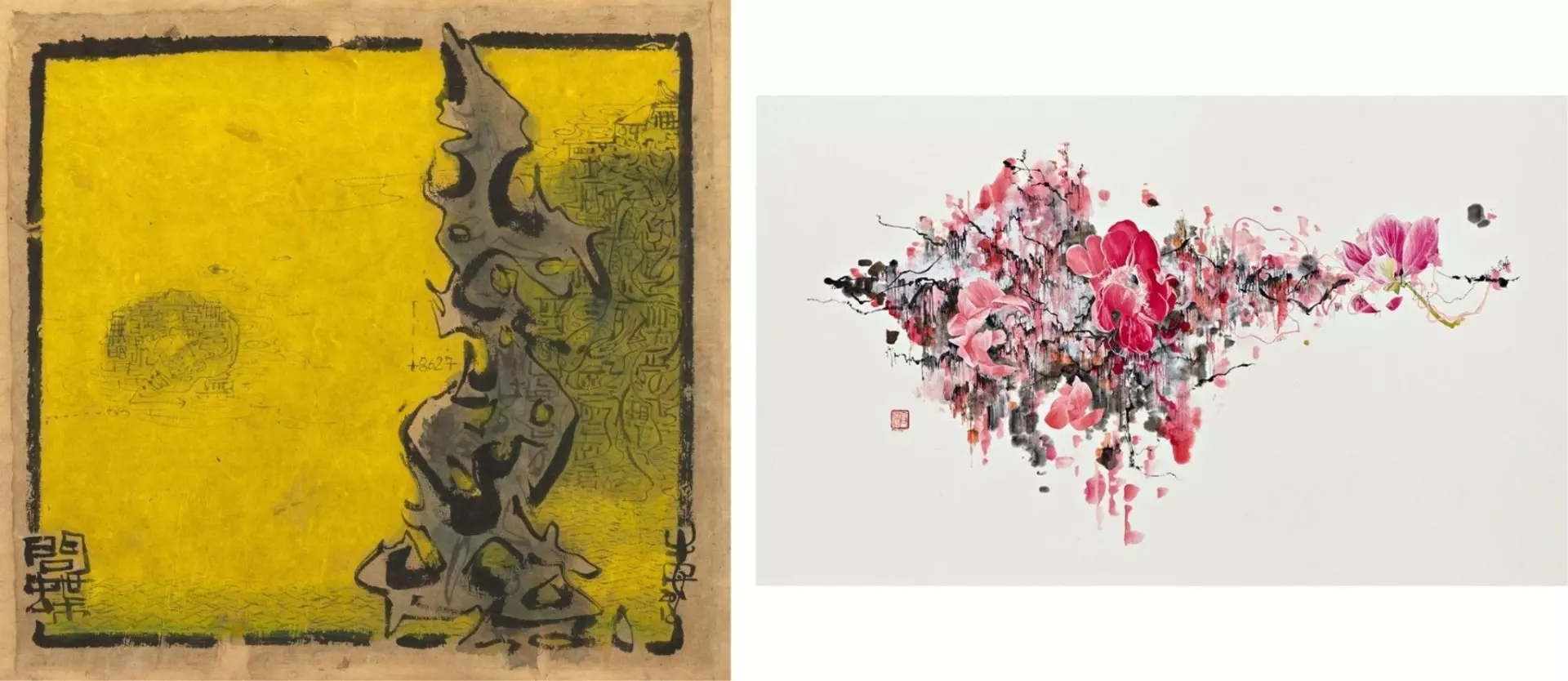

"Paper plays an active role in the creation of artworks. Artists test papers made of different materials and sizes to varying degrees before selecting the perfect one. Some even commission their papers to specific papermakers," says art consultant and curator Olivia Wang as she tells Vermillion of her 2020 documentary Unsung Heroes of Ink exploring the often overlooked role of paper in ink art. "Handmaking paper is very much an art form in itself... [and] xuan paper was historically the most prized type of paper, known as the 'King of Papers'."

Involving an 18-step process, there are three types of xuan paper — Shengxuan, Shuxuan, and Banshuxuan — classified according to their "ripeness", which affects the paper's absorbability, durability, and texture. It is no wonder xuan was selected as a UNESCO intangible cultural heritage, but its prestige doesn't mean it is elusive. Calligraphy and ink painting artist Ann Niu is but one of many who chooses to practice with the intricately beautiful xuan paper for its historic and artistic values, alongside the many artisans in China working to preserve the craft grounded in Chinese tradition.

Also registered as a UNESCO intangible cultural heritage, the Japanese washi paper's handmade process is a long and intricate one, but it creates paper that is tough, fine, and flexible. Deeply ingrained in Japanese culture, there are towns and villages in the country built around washi papermaking. All still being made today, the three main types of washi are — ganpishi, mitsumatagami, and kōzogami — named after their source plants of gampi, mitsumata, and paper mulberry. (xuan paper is also made from paper mulberry!)

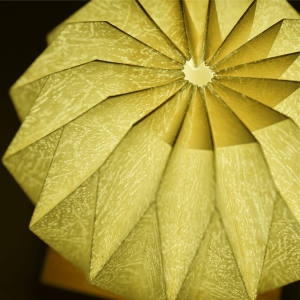

Widely used for the arts of origami, Shodo, Ukiyo-e, and many other Japanese art forms, washi is, too, a true art form in itself. Wataru Hatano, for example, is an artist and painter who makes his own washi paper, which "gives a special vibration to the painting." Now trained as a papermaker, Hatano also makes furniture such as tabletops, doors, and wallpapers, alongside objects like boxes and stationery to promote the many different uses of washi. Due to its earthy texture, washi is great for indoor paper screens, room dividers, sliding doors, and even lampshades that adorn Japan's stylish, historic architecture that we all know and love.

A slightly lesser-known heritage paper in Asia is wasli, which originated in India in the 10th century. Used specifically as a canvas for making miniatures — opaque/translucent watercolor paintings, wasli is handmade by pasting layers of sheets pasted together to create a thicker, stronger paper that is suitable for water-based mediums. Finally, the Wasli paper is burnished with either smooth glass or a sea shell for a shiny and smooth surface. What's more, it is an acid-free paper, which means it has archival qualities that are good for preserving artworks and documents. Paper-eating insects won't eat it because of a poisonous substance used during its preparation.

These handmade papers were the beginning of knowledge, information, and visual arts becoming more accessible and portable. As time goes by, they have become historic crafts that communities are fighting to preserve as art forms that tell stories about how stories were told in the olden days. In appreciating these Asian crafts, we are honoring a nuanced past that has endured, matured, and persevered through centuries; and in using these papers in our daily life—not just for writing and painting, but also in our furniture and interior design — we are paying tribute to the versatility in the paper, but also in our cultures.

HK$

HK$ SG$

SG$ US$

US$